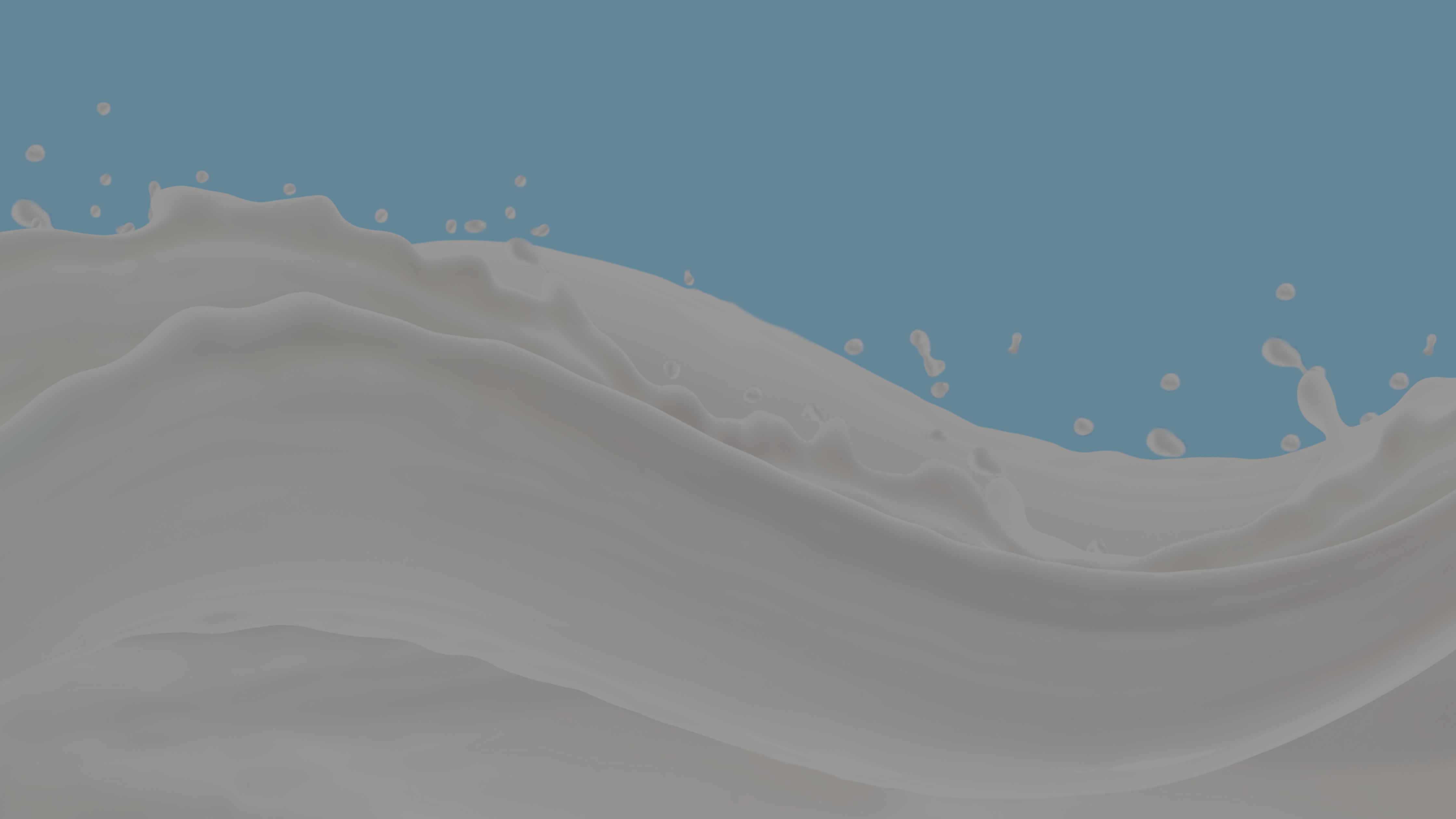

The global dairy seesaw has tilted heavily towards supply, as output is up in (almost) all major dairy-exporting regions. The last time that milk volumes grew like this was in 2017, when European production quotas were abolished the previous year. Through September 2025, year-to-date production among the top five milk-producing regions— US, European Union and the United Kingdom, Argentina, New Zealand, and Australia — is up 3,849 million metric tons, or almost 8.5 billion pounds (+1.73% YTD). Since this does not include spring flush data from the Southern Hemisphere, which is currently occurring, these year-to-date numbers are likely to continue increasing. Putting pen to paper, this wave of milk is enough to make an additional 850 million pounds of cheese (about 2/3 a month of US production) and 74 million pounds of WPC 80. Using the fat and skim portion instead would yield 466 million pounds of butter (almost three months of US churn output) and a little more than 770 million pounds of skim milk powder (about 4-5 months of US NDM/SMP drier volumes).

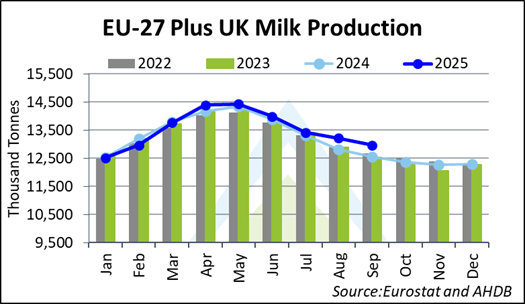

Diving into this data a bit further shows that volumes in the top five milk-producing regions have been up in every month of 2025, except February, which was dragged down by lower output from the European Union, particularly from the bloc’s top-producing nation, Germany. Starting in March, though, growth from the EU began to accelerate, pushing the global total up 0.7% YoY that month, and in April, collections from these key regions climbed 1.8%. The almost 2% increase continued through Q2, and rose to 2.2% in July. Once New Zealand ramped up in August, the year-on-year rate from these five regions grew to +3.2% and jumped to 3.9% in September.

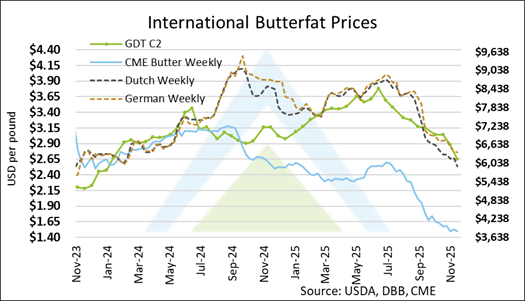

Milkfat has also been robust in the US and elsewhere. Year-to-date 2025, US fat pounds are up 305 million pounds and European fat pounds by nearly 200 million pounds through September (Sources: USDA/EU Commission). While New Zealand does not break components down to the milkfat and protein level, New Zealand 2023-24 Dairy Statistics published by Dairy NZ and Livestock Improvement Corporation (LIC), indicated the average Kiwi cow has a fat test of 4.99%. Extrapolating this out to a 2024 v. 2025 comparison results in a gain of over 20 million pounds of fat. With fat production up so markedly in all these regions, enough to make 640 million pounds of European-style butter, this helps to explain the swell of fat-heavy commodities and their falling prices. Given that some of these increases are driven by genetics, this increase could persist, even if milk production decreases.

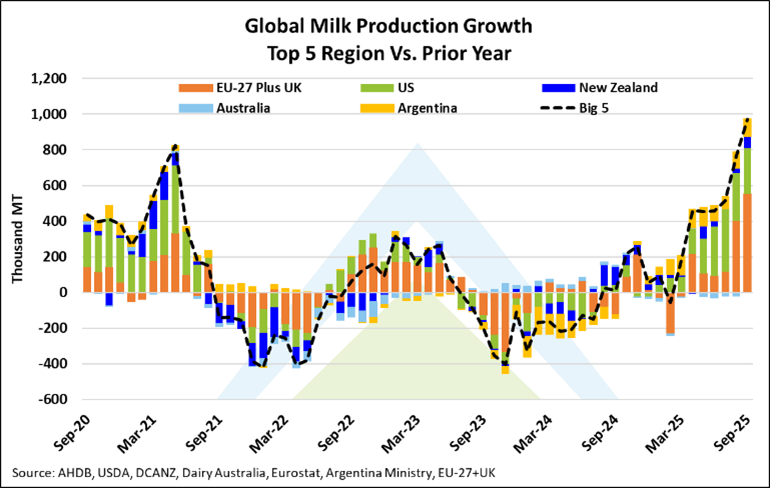

There is no immediate slowdown in sight. In the US, the Dairy Margin Coverage’s reported Income over Feed Cost was $11.52/cwt. in August, ranking in the 86th percentile relative to the past decade. Margins are forecasted to decline in the coming months, dipping below $10/cwt. in September, still above historical averages. But these numbers are forecast to slip under $9/cwt. in October and November, and under $8/cwt. from December 2025 to July 2026, which are historically low levels and at or below the 30th percentile over the past ten years.

However, revenue from cull cow and crossbred calf sales will prop up margins and lessen the sting of lower prices. Farmers should maintain above-breakeven level margins based on current and futures prices for feed and cattle, if the all-milk price remains in the $16-$17/cwt. range, which is the equivalent of $1.60/lb. cheese, $0.72/lb. whey, $1.47/lb. butter, and $1.13/lb. NFDM. Beef income is currently providing somewhere between $3-$5/cwt. to dairy farmers’ bottom lines and giving operations the oomph to stay in the black. While cattle markets have scaled back from their all-time highs in October, they remain well above average, providing generous income to dairy producers.

Typically, US farmers do not begin making decisions to reduce milk production until their on-farm margins become tight or negative. Without receiving a bad milk check yet, an $18-$19/cwt. all-milk price is not terrible. Add in beef revenue and lower feed costs than in previous years and it seems likely that it will be a few months before farmers feel the pinch and begin to adjust herd size lower.

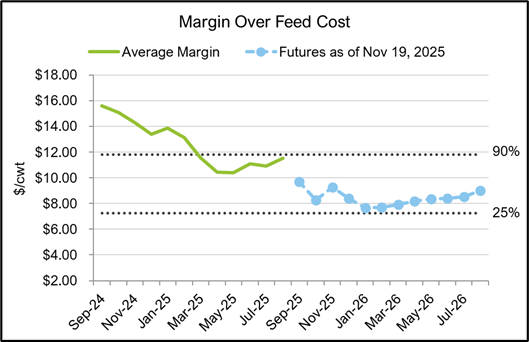

Elsewhere in the world, milk prices are also strong. In New Zealand, producers are coming off a record-high payout price of $10.16/kgMS from the 2024-25 season. In the 2025-26 season, the estimated payout is $9.50/kgMS. Much like their counterparts in the US, until these farmers receive the price signal to slow production, they will continue to take advantage of strong margins by producing more milk, and more milk may come due to idyllic pasture conditions in the 2025-26 season. This equates to an additional 455,732MT more milk thus far in the 2025-26 season through October (+14.8 million kgMs), a sizable contribution to milk production, with some of that swell due to favorable weather.

European prices have also been decent through September, averaging €0.5356/kg. in 2025. Market chatter suggests most European farmers’ cost of production sits closer to 0.36-0.42€/kg of milk, indicating very favorable profit margins in that sector too. The potential relaxation of the Common Agricultural Policy, which governs agricultural emissions of carbon and nutrients, is also encouraging farmers to produce more milk.

However, headwinds are blowing. EEX Gouda and Mozzarella cheese prices were at $1.6039/lb. and $1.5675/lb., respectively, as of the week ending November 21, much lower than earlier in 2025. CME Cheddar blocks have been rangebound for most of 2025. Kiwi Cheddar is at a sizable premium to these markets but is likely to fall through the end of the year as holiday demand wanes. At the second GDT auction of November, Fonterra’s Cheddar dropped by 2.7% to $1.96/lb. However, cheese pricing does not contribute to calculating farm-gate milk prices, meaning New Zealand dairy farmers will not increase production, i.e., respond, due to this premium.

Butter prices in the US are at 4+ year lows and are trading at a discount to blocks, a rare occurrence. At the same time, EU and New Zealand butter hold a premium of over $1.00/lb. to the US, although their prices have been in freefall too. German butter is down over a dollar from $4/lb. in early July, posting a price of $2.7583/lb. as of the week ending November 21. Kiwi butter is the most expensive in the world, with the C2 contract at the November 18 GDT settling at $2.66/lb., but it has also decreased significantly from early July, down $0.71/lb. over that period.

The other side of the equation is demand, and while dairy consumption globally in 2025 is decent and varies widely by commodity, it is insufficient to absorb all the milk. In the US, consumption is not growing significantly except for whey protein concentrates, and foodservice sales have been soft. In other parts of the developed world, diets are already high in dairy and without a new application or health claim, it is unlikely that consumption patterns will surge. Instead, they will continue their long-term trend of gradual increase. In places where dairy has not been a dietary staple, there is room for usage to grow, and cheese and whey protein concentrates are experiencing the most significant upswing.

With supply easily outpacing current demand, a glut of milk and dairy products is expected in the coming months. Big supplies relative to average demand will lower prices from where they are today; put differently, the bottom has not been put in yet, and supply will need to adjust. The question is: from where, when, and how?

In the US, attrition seems likely in 2026, given the low slaughter rates and the largest herd since Q2 1993. HighGround forecasts that the herd will be close to 9.45 million head by the end of 2026, slowing the milk spigot, and a drop of 131,000 head from September 2025 data. And the impact could be even larger, particularly if feed costs rise or cattle and beef imports are adjusted upward, pushing those markets, and dairy farmers’ extra margins, lower. Rapid contraction has happened before. From May 2021 to January 2022, cow numbers dropped by 141,000 head, and from December 2008 to December 2009, they fell by 249,000. Farmers nearing retirement are most likely to liquidate their assets. A jump in feed costs or a drop in beef revenue will create havoc, though, and are wild cards to watch for, as they would cause a greater exodus of dairy farms.

In Europe, the storyline will be similar: older farmers who had been considering retirement may be ready to pull the trigger if the market experiences a downturn. In 2026, HighGround anticipates decent first-half volumes across the pond and declining production during the latter half of the year, which is expected to curb the milk wave.

New Zealand is trickier to predict, as much will depend on where pay prices wind up in the 2025-26 season. That said, farmers will likely be able to lower margins by feeding less Palm Kernel Expeller (PKE) and drying off cows sooner, which will also influence milk flow. SGX New Zealand milk price futures for the 2026-27 season (and beyond) are lower, under $10.00/kgMS, and if these prices come to fruition, will cause farmers to make different decisions.

Regardless of locale, prices are poised to move lower, and at some point, that will catch up with producers in these key milk-producing regions. HighGround anticipates that although global milk production may increase for over a year, likely through the first half of 2026, falling prices that have already started will weigh heavily on producers, forcing consolidation. This will cause a shift in supplies next year, and global collections will be flat to down as exits and culling occur during the latter half of 2026.